I have been thinking, and wanting to explain if I can, why I am so endlessly fascinated with Budapest. There are many beautiful places and things in the city: bridges, parks, sculptures, as well as buildings. But the allure of Budapest for me is not just its isolated treasures. Somehow the city itself--almost in its entirety--feels like an unfinished, never-finished piece of art.

I say this knowing Budapest does not have the cohesive historical appeal of a city like Krakow or Prague, with their intact medieval cores. Nor does it have the historical depth of a city like London or Paris with their Gothic cathedrals or centuries-old palaces. Of course there are old buildings in Budapest: Roman ruins, Baroque churches. But the overwhelming feeling of Budapest (at least in the historical Pest) is that of something put together recently--almost within living (and dying) memory.

The capital city of Budapest was established in 1873, with the unification of Buda, Pest, and Obuda. Between then and World War I, Budapest was the fastest growing city in Europe, increasing its size from about a quarter of a million people to a population of about a million. The city was consequently very crowded, and there was a huge building boom. The novelist Sandor Marais writes that in the early twentieth century"building went on at every street corner, the capital city of the great, rich, happy empire was having its image built, feverishly fast, and on a greatly exaggerated scale." What must it have felt like to be alive in that great civic transformation? And what did all those buildings look like?

At first, architects looked to established styles and built neo: Gothic, Italian Renaissance, Baroque, etc. Sometimes the buildings were coherently from one period, and are now called Historicist.

Sometimes the buildings anachronistically combined many periods and are now called Eclectic.

Eventually, however, architects in Budapest, as they did in other European cities wanted something new: Arts and Craft, Art Nouveau, Jugendstil, Secession. Moreover architects wanted something that was national, Hungarian. But what was the national style of Hungary?

This was a difficult question because Hungary was part of a dual monarchy: the Austro-Hungarian Empire, AND because Hungary itself was a shifting concept: a country that in its history has included countries now known as The Czeck Republic, Slovakia, Ukraine, Serbia, and Romania. Trying to find Hungarian identity in the midst of all this multi-ethnicity was, and remains, a fraught issue.

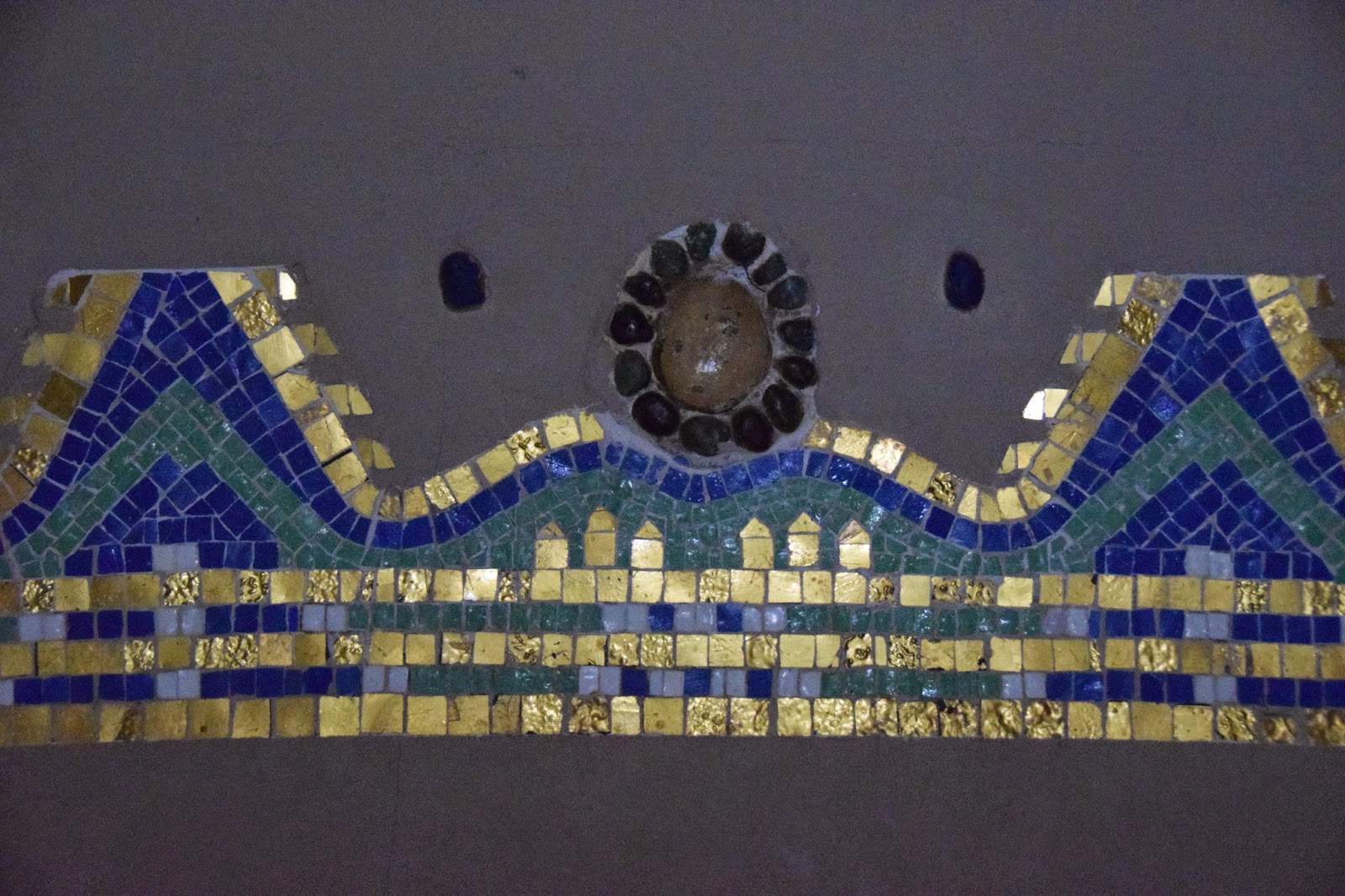

The genius of Hungarian architecture who first really addressed this question was Odon Lechner. Lechner looked to the identity of Hungary in its supposed origins in Persia and the orient and in its enduring, primarily Transylvanian, folk traditions. He was also aided by contemporary technology, especially Zsolnay tiles which allowed him to make his buildings bright, vivid and colorful. Other architects followed Lechner, not all with his intellectual and aesthetic rigor.The result is a city of varied architecture--quoting, pointing, speaking a variety of aesthetic and national languages.

Hungarian architecture is extremely figural and highly decorated. And most of the detail is on the facade. But most of the buildings that went up in the boom were brick covered with plaster and stucco, and plaster crumbles if not maintained. The result is It is a city whose buildings are almost all in various states of decay. A few are well maintained; some have been maintained hit-or-miss; and some are virtually shorn of their identity.

Twin" buildings, one restored and the other not.

Thus as one walks Budapest's streets, she must look carefully. What is missing from this building? Are there hints of what it might have been? What is the neighborhood? How were these buildings used? What made them beautiful or desired to the owner's eye? The city is immersive and requires active aesthetic and intellectual engagement. It always offers a surprise if one looks carefully. Some beautiful image that is anchored in history but hovering just beyond the gaze of what a contemporary viewer can see.

.JPG)